Following my daughter’s chiding in her last post I rush to put pen to paper about Sir Thomas More; the more so since it is particularly apposite to recent political events.

It is not a play that immediately springs to mind when Shakespeare’s works are discussed. Indeed when I was studying Shakespeare at school in the 60’s neither it nor many of the issues it raises were mentioned at all. The authorship debate I first learned about from Kipling’s short story The Propagation of Knowledge (spoiler alert I am at one with King the English teacher on this; Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare and the rest is “rancid Baconian rot”).

But in the last ten years Sir Thomas More has become almost notorious, and worthy of a little of the study it bypassed in my schooldays. So to start with a few facts (and by facts I mean what appears to be generally agreed by reasonably qualified experts. There is as much woo on Shakespeare websites as there is on alternative medicine ones).

- The play was written between 1596 and 1601 by Anthony Munday. It was revised by Shakespeare, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker and Thomas Heywood some time after the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603. (This group of playwrights deserves another blogpost. They all collaborated with each other in the late 16th and early 17th Dekker is now probably the name most likely to be recognised after Shakespeare. But Munday – actor, draper, spy, royal messenger, “Poet to the City [of London]”, one of the authors of Sir John Oldcastle which was published in 1619 under Shakespeare’s name, and with Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (yes that one) as his patron – was another extraordinary character in the cast of Elizabethan playwrights).

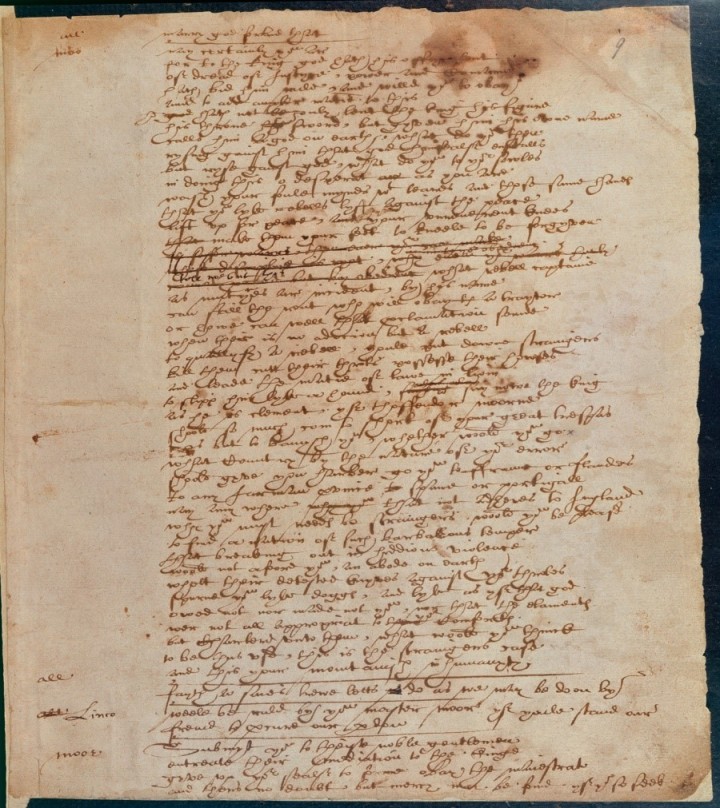

- The surviving play script is unique in containing three pages which are (consensus of informed opinion apart from those who attribute Shakespeare’s plays to another author) in Shakespeare’s own hand.

Image courtesy of the British Library, see more at http://www.bl.uk/collection-items/shakespeares-handwriting-in-the-book-of-sir-thomas-more

- After the turgid opening of the play (my opinion) the text on these three pages stands out. It is Shakespearian in style and quality; and this is born out not just through reading it but also by analysis of word frequency and spellings (and handwriting comparisons, but the other samples of Shakespeare’s hand are so few – half a dozen signatures – that this seems a weak argument to me by comparison with the other factors).

- The Master of the Revels, Edmund Tilney, made this manuscript comment on the first page of the Shakespeare holograph

Leave out the insurrection wholly and the cause thereof, and begin with Sir Thomas More at the Mayor’s sessions, with a report afterwards of his good service done being Sheriff of London upon a mutiny against the Lombards – only by a short report, and not otherwise, at your own perils. E. Tilney.

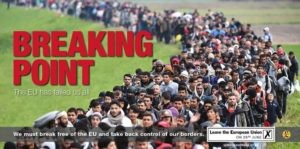

The topic of immigration was a hot political one then as now and clearly he feared the impact of the play on the volatile situation at the time with street rioting against new waves of immigration, principally Huguenots. In the end he appears to have banned public performance of the play entirely.

- The play was thus probably never performed during Shakespeare’s lifetime or afterwards – indeed the manuscript vanished from sight until it surfaced in 1728 in the hands of a London book collector, John Murray. He donated it to Edward Harley who subsequently gave all his manuscript collections to the British Museum in 1753. It was not published until 1844 and not performed until the 20th

But none of these are the reason for the current interest in the play. In Act III Scene 2 Surrey says “Poets were ever thought unfit for state”, but recent debate about the play relates entirely to its continuing political significance. Not the debate about the conflict of duty between Church and State; ironically this is never overtly mentioned in the play though potential audiences would clearly have been well aware of it. It is Shakespeare’s section that has triggered the interest.

To set the scene. Immigrants from Lombardy are spreading disease and crime in London. The good patriotic citizens riot and burn their houses down. Thomas More goes out to speak to the crowds. And this is (some of) what he says.

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to th’ ports and coasts for transportation

Remind you of anything?

God this made my blood boil…

Bur of course More was seeking to encourage sympathy for the wretched refugees, not stoke the fires of intolerance and xenophobia. And then he really rips in to his audience

You’ll put down strangers,

Kill them, cut their throats, possess their houses,

And lead the majesty of law in lyam

To slip him like a hound;

alas, alas, say now the King,

As he is clement if th’offender mourn,

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you: whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbour? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers, would you be pleas’d

To find a nation of such barbarous temper

That breaking out in hideous violence

Would not afford you an abode on earth.

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, not that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But charter’d unto them? What would you think

To be us’d thus? This is the strangers’ case

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

Project Gutenberg has the full text.

So William Shakespeare, that most English of Englishmen, once again strikes to the heart of our current concerns, with a powerful plea for humanity and tolerance. It is ironic indeed that those who now claim to be most attached to and concerned for England pay least attention to what its greatest writer has said. It is also ironic that Shakespeare ostensibly makes the case on “Do as you would be done by” rather than on straightforward humanitarian grounds; Tilney and his masters were more concerned about ensuring obedience to civil rule than actually helping refugees. It is dangerous to project modern views on past writers. But I think Shakespeare slipped quite a lot more into the mouth of Thomas More.

One thought on “Poets were ever thought unfit for state”